The Credibility Test Facing the Election Commission

Today, public confidence is being tested once again by an uncomfortable debate: is the Chief Election Commissioner truly politically neutral, or is he perceived as aligned with one particular camp — specifically, the BNP? This question is not a slogan. It is a credibility issue with serious implications for turnout, acceptance of results, and the stability of the political environment.

When Neutrality Becomes a Question: The Credibility Test Facing the Election Commission

In any democracy, the Election Commission is more than an office. It is the referee. When the referee’s neutrality is questioned, the match may continue — but the crowd loses trust, and the result loses legitimacy.

Today, public confidence is being tested once again by an uncomfortable debate: is the Chief Election Commissioner truly politically neutral, or is he perceived as aligned with one particular camp — specifically, the BNP? This question is not a slogan. It is a credibility issue with serious implications for turnout, acceptance of results, and the stability of the political environment.

Why neutrality is not a “nice-to-have”

Neutrality is not a ceremonial virtue. It is the foundation of: equal treatment of parties and candidates,

credibility of voter rolls and constituency boundaries,

impartial enforcement of campaign rules,

and public acceptance of final results.

Once a Commission is viewed as partisan, even correct decisions appear suspicious — and that perception alone can damage the process.

The weight of historical expectations

Bangladesh has seen Election Commissions led by figures who, regardless of controversy around their eras, became reference points in public memory. Names like Justice Abdur Rouf and M.A. Sayed often surface in discussions about how Election Commissions are expected to stand above party interest.

For this reason, some citizens hoped the current Chief Election Commissioner would define his tenure with a similar “institution-first” legacy: fairness, restraint, and distance from party machinery. Instead, those expectations are giving way to disappointment among observers who believe the Commission is not communicating, acting, or enforcing rules with the level of visible impartiality the moment demands.

Perception matters: the problem of political proximity

A key reason these doubts persist is not only decisions, but perceived proximity — professional and political — between the Commission’s senior leadership and partisan networks.

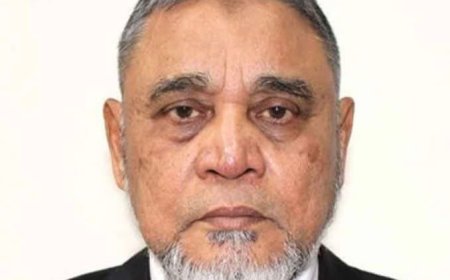

One example often raised in political conversations is former Energy Secretary A.M.M. Nasir Uddin, described by critics as a bureaucrat who was highly favoured during Begum Khaleda Zia’s tenure. Some accounts further claim that if the BNP had contested the 2008 national election independently, he may have been considered for nomination in the Cox’s Bazar-2 (Kutubdia–Maheshkhali) seat under the “Sheaf of Paddy” symbol.

However, because of alliance politics, this constituency was reportedly conceded to Hamidur Rahman Azad of the BNP’s ally Jamaat-e-Islami.

Even if parts of such narratives remain disputed or politically contested, the broader issue is this: when the public believes senior figures and influential networks are tied to one side, neutrality becomes harder to prove — even when actions are lawful.

Alliance politics: when seats become bargaining chips

The Cox’s Bazar-2 example also exposes a deeper truth about Bangladeshi electoral culture: constituencies can become currency in alliance negotiations. While alliances are not illegal, the public often reads them as transactional and opaque.

When institutions like the Election Commission are seen as drifting into the gravitational pull of such power-bargaining, it reinforces cynicism:

that elections are managed outcomes,

that administrative decisions mirror political deals,

and that the system serves parties rather than citizens.

What a neutral Commission would do — visibly and consistently

If the Election Commission wants to restore confidence, it must practise neutrality in a way that is visible, not merely stated. That means:

Transparent decision-making

Publish detailed rationales for key decisions, including enforcement actions.

Equal enforcement

Demonstrate consistent application of rules across parties — not selective intensity.

Open data and public audits

Make electoral data accessible for scrutiny: voter roll processes, complaint handling, and investigation outcomes.

Communication with restraint

Avoid statements or postures that sound defensive, political, or dismissive.

Institutional distance

Ensure no appearance of political favouritism in appointments, meetings, or informal engagement.

Neutrality is not only what you do — it is what people can reasonably see you doing.

The legacy question

Every Chief Election Commissioner eventually faces a final judgement in public memory: did you protect the institution, or did you serve a momentary political interest?

If the perception grows that the Chief Election Commissioner is politically aligned — whether with BNP or any other party — it will not merely stain a person’s legacy. It will weaken the credibility of the Commission itself, and that damage outlasts any single tenure.

A democratic election is not only about ballots. It is about belief. And belief cannot be commanded — it must be earned.

Editorial Note: This article is an opinion/analysis piece. References to individuals and political relationships reflect public discourse and allegations that may be disputed. We welcome corrections and credible documentation.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

1

Like

1

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

1

Love

1

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0